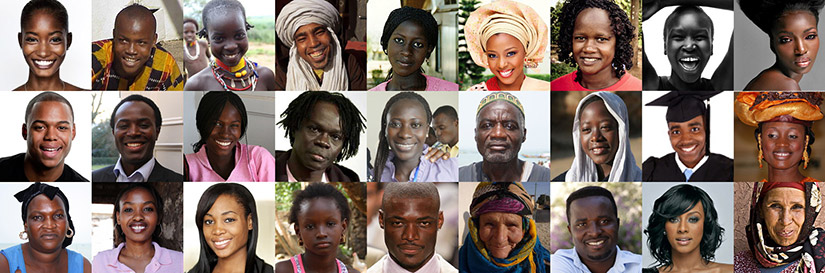

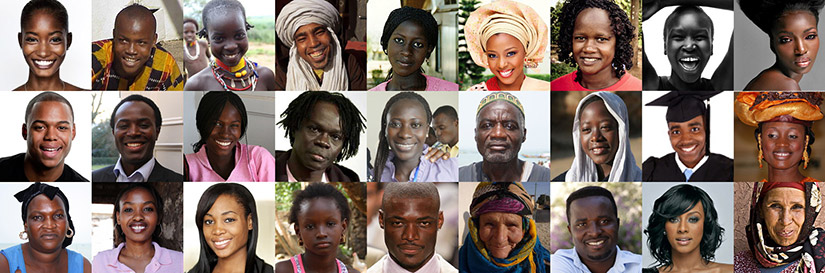

The “Year of Return, Ghana 2019” was a prominent spiritual and birthright journey that invited the global African family home to the African continent. Initiated by the Ghanian government and adopted by other West African countries, the Year of Return was conceptualized as a way to mark the 400th anniversary of the arrival of the first enslaved Africans in Jamestown, West Virginia.

While this part of our collective history is tragic, the Year of Return sought to celebrate the many contributions of the people who were taken from Africa against their will. For example, they commanded a language they had never before heard and used it to write poetry and plays, birth entirely new genres of music, and fight for social justice.

Another form of language and communication was found in food. Both enslaved and free Black Americans survived on food that was scarce, discarded, or unwanted. Adding the memories and vignettes of their African roots and heritage, they created, influenced, and popularized cuisine that has defined not only American culture across the country, but celebrates the cumulative resilience of all the victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade who were scattered and displaced throughout the world in North America, South America, the Caribbean, Europe, and Asia.

James Hemings (1765-1801) was a chef to Thomas Jefferson, trained in Paris, yet he was born into slavery and lived much of his life enslaved. At thirty years of age, he negotiated for legal emancipation and began his life as a free man. He traveled and pursued his career as a chef, but unfortunately his career and life in freedom were short due to his tragic and untimely death at age thirty-six.

While in Paris, James Hemings was trained in the art of French cooking. After three years of study he became the head chef at the Hôtel de Langeac, Jefferson’s residence that functioned also as the American embassy. Here his dishes were served to international guests, statesmen, authors, scientists, and European aristocrats.

Hemings – along with many other highly trained enslaved individuals who succeeded him in Washington and at Monticello – serves as inspiration to modern-day chefs and culinary historians alike, and these early African American chefs helped create and define American cuisine as we know it today.

Sourced from:

https://www.yearofreturn.com/

High on the Hog, Netflix original documentary. Episode: 3 “Our Founding Chefs”, aired May 26, 2021, by Stephen Satterfield