By Erin Richards

A Houston teenager preternaturally keen on research and activism was at home this summer, searching for a bill about transgender student-athletes, when he stumbled on something on the Texas Legislature’s website related to his own schooling.

Siddhanth Pachipala, who is 16 and the son of immigrants from India, was surprised to read the education bill proposed by Texas Senate Republicans. It strictly limited what teachers could talk about in public school history classes, including the civic accomplishments of minority populations, Native American history and the history of slavery.

Pachipala knew of the recent firestorm over critical race theory in schools. But the bill seemed to be denying important historical events.

“They were crossing out the history of white supremacy, the Ku Klux Klan and the civil rights movement,” said Pachipala, who started a petition to fight the proposed legislation on Change.org. Almost 70,000 people had signed on as of Thursday.

The Texas bill and similar Republican-led legislation in other states have prompted pitched battles over how race, racism and slavery are taught in public schools. The disagreements are particularly contemptuous around how the founding of America is taught and the extent to which racism influences society today.

But among well-respected scholars, there’s considerable agreement about what constitutes good instruction of America’s beginnings. Long before “critical race theory” made its way into state legislatures and onto cable news, more than 300 history professors, political scientists and civics experts were at work on a national road map to help guide U.S. history and civics teachers.

There are no national social studies standards that mandate which events and historical figures should be taught in each grade, and previous attempts have ended in disagreement. The Educating for American Democracy report made that a central focus. The report, published in March, identifies the fundamental civic knowledge necessary to have civil disagreements about historical and current issues.

The scholars united around a goal of “reflective patriotism,” or loving one’s country while recognizing and debating its flaws.

“To prepare informed and engaged citizens, we need to encourage reading, listening, talking and debating,” said Paul Carrese, a conservative professor of political thought at Arizona State University and a key voice in the initiative.

Education, history and civics professors from various backgrounds agree good American history classes contain other key elements. Here are some of them:

A focus on political knowledge and primary sources – from many views

Good history lessons build political knowledge through exposing students to materials from primary sources diverse in race, gender and experience. That means analyzing and debating historical documents, accounts and letters instead of just reading a modern textbook or memorizing lists of facts.

It sounds basic. But American students don’t know much about their own country. In eighth grade, 85% of students scored below proficient in U.S. history in 2018, national exam scores showed.

They know even less about the history of slavery.

In a 2016 poll, only 8% of high school seniors correctly identified slavery as the central cause of the Civil War, according to a nationwide poll and report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, an anti-racism nonprofit.

That’s because many teachers find race, racism and slavery difficult to teach; many textbooks skirt the subject; and many state standards around the subject are vague, scholars say.

Wrestling with the clash between ideals and reality in America’s founding

Some conservatives believe teaching the founding of America has become too negative and focused on slavery. Many say history lessons make white children feel guilty about their ancestors enslaving people. Others see the discussion of concepts like systemic racism and white privilege as indoctrination aimed at promoting social-justice activism.

But an increasing number of teachers, particularly those in schools that predominantly serve students of color or who are people of color themselves, believe teaching honest American history means illuminating the role race played in it.

Good history teaching should help students celebrate the ideals of the Founding Fathers while acknowledging the ways in which America has failed to live up to its promises of liberty and justice for all, said David Bobb, president of the Bill of Rights Institute, a nonpartisan nonprofit in Arlington, Virginia, that supports social studies teachers.

“But teachers should support freedom and equality for all – so in that sense they’re not neutral,” Bobb said. “It’s about channeling a love of country, but in a way that’s reflective.”

The founding of the country is “a fundamentally complicated reality,” said David Griffith, a senior researcher at the conservative Fordham Institute in Washington, D.C. The group recently reviewed state social studies standards and rated 19 states as inadequate.

Teach the facts, Griffith said, and avoid lionizing controversial figures or passing judgment on people who lived 200 years ago.

Giving students tools to debate the legacy of slavery

Giving students tools to debate the legacy of slavery

But what about the extent to which the vestiges of slavery contribute to racial and economic inequality?

Good teaching should give students the knowledge and skills to debate that themselves, said Jane Kamensky, a history professor at Harvard University.Is inequality in the U.S. a result of the structures of our government or more because of individual human acts?

Students must understand how enslavement influenced the American colonies and the global trade system. They need to know how the institution worked and how it ended. They should learn what America after slavery looked like and how long it lasted. They must understand how people participated in the struggle for civil rights and what it accomplished. They also need to know how Black people, women and immigrants overcame seemingly insurmountable barriers throughout the nation’s history, Kamensky said.

“Students need to know all that before they can wrestle with how much we still carry the shadow of slavery with us,” Kamensky said.

Encouraging ‘grace and empathy’ among students

Good history teaching also means inviting students, if they’re comfortable, to share narratives and perceptions from their own lived experiences, said Anika Prather, an instructor at Howard University whose research focuses on literacy in Black students. Personal experiences, of course, are likely to be different for children of color than for white children.

“Believe our students,” Prather said in a recent webinar hosted by the Bill of Rights Institute about how to teach race in history class.

And ask how white students feel in these turbulent times, Prather added.

“It’s important to make sure there’s a spirit of grace and empathy permeating the entire classroom,” she said.

Respectful, inclusive class activities

Ethically questionable or careless history class exercises have captured news headlines, such as when students are asked to reenact the trauma of enslaved people.

There are better hands-on ways to help children think holistically about the various viewpoints and motivations of the people in early America.

Fifteen to 20 years ago, many teachers built history lessons around learning basic facts, said Heidi Trevithick, a teacher at J.K. Mullen High School, a private school in Denver. She has long encouraged activities that expose students to different perspectives.

In one exercise, Trevithick has students research the social, political and cultural positions of groups of people at the end of the Civil War. She then has them role-play the conversations their group would have about the future of Reconstruction. Students pick groups to research, such as enslaved people who gained their freedom in the North, Southern women and male plantation owners.

“It gets students speaking from perspectives of people at the time,” Trevithick said.

Jarvis Givens, a Harvard University education professor who studies the history of American education and African-American history, said teachers also should consider parts of American history that have long been significant for Black people. That includes lessons on Nat Turner, the Haitian Revolution and the leaders of the Colored Conventions movement (a 19th-century campaign for Black civil rights).

Givens said those subjects were “an important part of history for African American teachers in the 19th century through Jim Crow, and yet they were studiously omitted from the dominant curricula.”

A comprehensive curriculum – and knowing its limitations

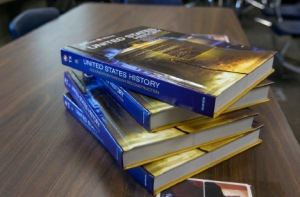

American history, like all subjects, is guided by a curriculum, which includes texts and activities and teacher resources. Some are better than others.

O Institute for Education Policy at Johns Hopkins recently reviewed 11 common civics and social studies curricula and released the results of five publicly, including from textbook giant McGraw Hill and iCivics’ one-year middle-school course.

The Johns Hopkins review found strengths and weaknesses in each one and recommended ways in which each could be used.

The Hopkins team also reviewed the 1619 Project educational materials, which stemmed from a series of New York Times stories in 2019 that framed the founding of the country through the context of slavery.

The project won a Pulitzer Prize but faced some critiques for omissions and factual inaccuracies – several of which the Hopkins team referenced. Some conservative legislatures and school boards have gone further, banning the use of the 1619 Project as well as critical race theory, an academic legal theory that examines the influence race has on society and institutions. (Few teachers are actually teaching the theory.)

The 1619 materials raise important concerns but are too limited to be considered an actual curriculum, the review concluded.

“The power of race and the tragedy of enslavement and its long legacy should be taught,” said Ashley Berner, director of the institute at Johns Hopkins. “But if you use race as the explanatory narrative, it needs to be set alongside other explanatory narratives” from different points of view, she said.

Good history classes rarely rely on one curriculum wholesale, said Art Worrell, director of fifth to 12th grade history at Uncommon Schools, an East Coast charter school network serving about 20,000 students. He said he likes combining resources from the Stanford History Education Group.

History curriculum should frequently be tweaked, he said, and that’s true especially now, when the country is gripped by political, racial and social upheaval.

“The past year and a half since the murder of George Floyd has been an important moment of reflection – for our values, our curriculum and everything we do to serve kids in our different regions,” he said.

Where do scholars and teachers take it from here?

Scholars and researchers say a bigger national conversation is needed on the state of American social studies instruction, as there’s still a major lack of consistency.

Vague state social studies standards that offer little direction are one major problem, according to the Fordham Institute’s review. It identified exemplary U.S. history and civics standards in only the District of Columbia and four states: Alabama, California, Massachusetts and Tennessee.

Meanwhile, two contentious presidential elections, national upheaval around racial justice, an insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, misinformation online and prejudice and hatred against subgroups of people are threatening American democracy, said Peter Levine, associate dean at Tufts University and an expert in civics education.

Bitter political divides around the response to the coronavirus pandemic haven’t helped.

“We have never been in so much peril of losing our republic as we are right now,” Levine said during a webinar about social studies education hosted by Johns Hopkins University.

“We need better civic education than we’ve ever had before, in a more difficult environment than we’ve ever had before.”

Contact Erin Richards at (414) 207-3145 or erin.richards@usatoday.com. Follow her on Twitter at @emrichards.