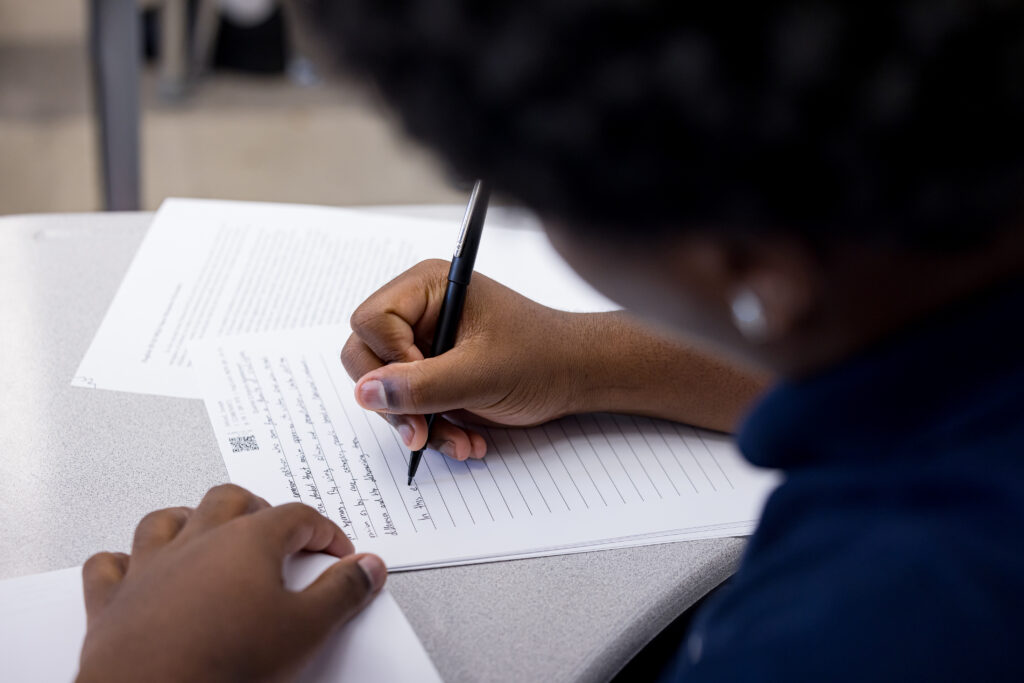

When I decided to introduce Environmental Science into our high school STEM curriculum in 2004, I did not fully appreciate the impact of teaching students how to access knowledge through direct skill instruction and practice as the answer to building true STEM expertise. Students took notes in my classes, even as young fifth graders, but they simply copied from chalkboards and projectors and then regurgitated information I sometimes mistook for understanding. A lot of information needed to be given to students, which was the easiest way to get it to them. While we still engaged in projects and labs, assigning the task of note-taking would lead to internalized vocabulary, retained content, and internalized understanding of the science concepts. Five years later, I asked our Science department to embrace the instructional practice of directly teaching note-taking in all of our classrooms as a critical skill in science, along with data analysis, graphing, experimental design, and more.

When I decided to introduce Environmental Science into our high school STEM curriculum in 2004, I did not fully appreciate the impact of teaching students how to access knowledge through direct skill instruction and practice as the answer to building true STEM expertise. Students took notes in my classes, even as young fifth graders, but they simply copied from chalkboards and projectors and then regurgitated information I sometimes mistook for understanding. A lot of information needed to be given to students, which was the easiest way to get it to them. While we still engaged in projects and labs, assigning the task of note-taking would lead to internalized vocabulary, retained content, and internalized understanding of the science concepts. Five years later, I asked our Science department to embrace the instructional practice of directly teaching note-taking in all of our classrooms as a critical skill in science, along with data analysis, graphing, experimental design, and more.

Much like the skills of data analysis, graphing, and designing experiments, note-taking is a skill that transcends topics, content areas, and grade levels. Note-taking is a skill that provides students with access to information and a keen pathway to constructing understanding and, therefore, reinforcing new content. Through note-taking, students can distill key ideas to be active participants during class and deepen their knowledge through collaboration with peers after class. All of these activities help to build their expertise in any field for a life-time.

Traditionally, note-taking has become a “busy work” assignment for students, either in class or as homework. I had been having students read and take notes since they were 5th graders in my first science class in 1997. Without proper guidance or instruction, students are often assigned the typical, “Go home and take notes on pages X-X”. For me, this was often followed, the next day, by my giving students the exact notes that some students may or may not have already taken, either in the form of a slide deck or fill-in-the-blank guided notes, something resembling a copy-paste of information from textbook to a notebook. My students were not taught how to take notes or use them. This was a big mistake on my part back then. To be clear, I didn’t only assign and give notes in classes. Students actively participated in discovery, science labs, ethical scientific discussions, and projects. However, when I was assigned note-taking or gave notes, I can now say that I didn’t honestly know what knowledge was gained, nor did I truly assess it.

Much like note-taking, teaching is a skill; the more you do it, the better you see your mistakes and learn from them. I eventually learned the power of note-taking and how to ensure this skill builds knowledge and expertise in my students. As science teachers, there are three key steps we can take to ensure that this skill is developed in our students:

1. Plan for purposeful note-taking:

Planning ensures that you have determined the format, the unit, and how often and where students will practice this skill throughout the unit.

- What format of note-taking works for my content area?

- I liked a combination of the Cornell Note-taking method and the SQ3R method. I then created a template for students to model their notes after.

- What unit/topic will I use to introduce the skill?

- I suggest doing this early in the school year or at the top of the quarter so that students can practice this skill throughout the marking period/year.

- Have I created the exemplars and instructional signage to teach students how to take notes the way I want them?

- Create models and exemplars of your notes. Model the thinking for students around what you chose to write down and what questions you asked yourself to determine that. This is a skill; like any other skill, you would be clear about how to do it and why you do every step. This helps students internalize the process better.

2. Plan for students to use their notes in class:

Identify how students can receive feedback on their notes and learn and practice using them as tools for enhancing and deepening their understanding.

- Open notes assignments

- Content presentations in which you only ask questions, and the students use their notes to fill in, debate, and discuss the answers

- Open notes quizzes where students only receive credit for answers highlighted in their notes

3. Show students how to use notes to generate study tools and be a resource for understanding:

Studying is a skill, too. Let students use their notes to create study tools and then have them practice at home and in class with their peers.

- Provide time for group study sessions where notes are used to generate study tools (flashcards, Kahootz games and quizzes).

- Have students go through their notes to identify gaps in their understanding and to use that then to generate questions around the content to ask the teacher or peers.

From Theory to Practice: Real Life Examples

Start Note-Taking Strategies Early

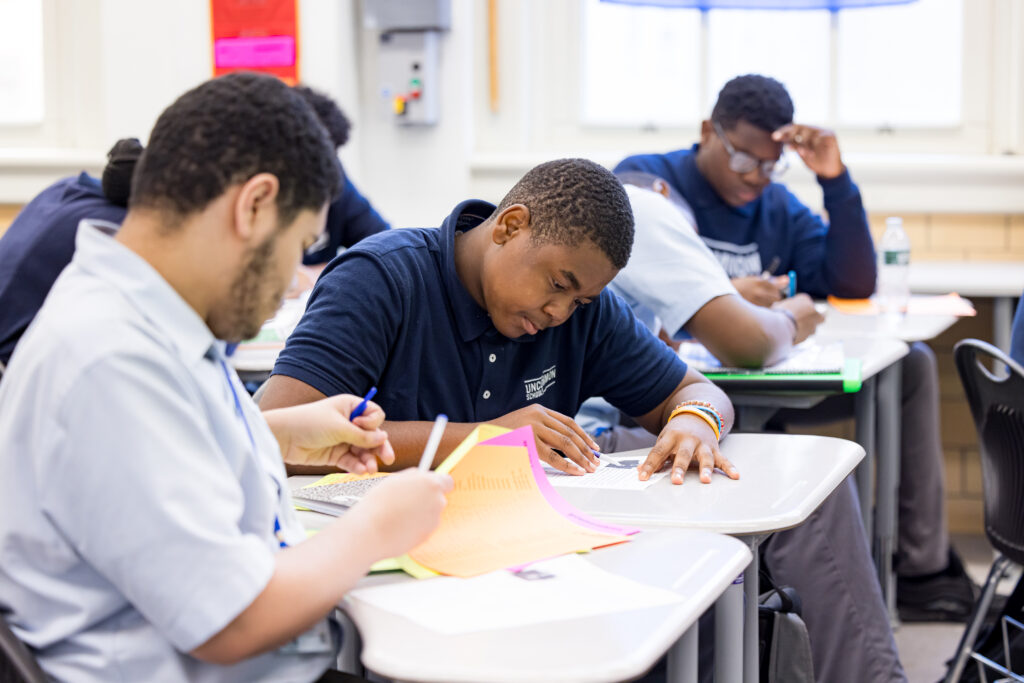

Zach Rogers teaches middle school science. Transitioning from elementary to middle school can be difficult for students, especially with independent tasks like note-taking. So, Zach builds time into the beginning of the school year to explicitly show students how to take notes: he shows them how to create a table of contents and rolls out the overall organization of their notebook. From there, students begin the practice of note-taking. At the start of the year (and for younger learners), this looks much like copying. For students who write more slowly or need more time to process, Zach offers three options: copying the teacher’s notes, copying from a partner (a strong note-taker), or attending study hall to complete the notes. These choices are particularly beneficial for students who need accommodations: they keep both the rigor and access high. “Some of the strongest notebooks I’ve seen have been from students,” Zach says, and their success in this area fuels greater investment in the content.

Regular notebook checks add an extra measure of accountability. Zach quickly sees which students keep organized and complete notes and which ones need follow-up. The condition of the students’ notes gives him a quick overview of the room’s understanding. But Zach doesn’t stop at having students take notes; they must use these notes to fuel their knowledge.

“If we’re having a class discussion, students know they can refer to their notebook,” Zach says. “They don’t have to spend their thinking time trying to remember a key vocabulary term. And before every internal assessment, we have a pause day. Students create flash cards based on their notebook, and they quiz each other.”

Encouraging students to use their notebooks as a tool has dramatically increased student independence. Students are much less likely to ask Zach for homework help; some have even involved their family members as study partners. While note-taking is more teacher-led at the start of middle school, teachers like Zach gradually move students away from copying the board and toward methods like guided notes and other ways of sharing information that require students to prioritize the most important information as they write.

Build Muscle Memory- Use Notes Throughout the Lesson

Build Muscle Memory- Use Notes Throughout the Lesson

Former high school science teacher and current Science Director Lauren Wong didn’t save student note-taking for the mini-lesson or experiment. She had students use notebooks all period. Lesson launches allowed students to use their notebooks to quiz themselves and their partners or prepare for a class oral review. In addition to traditional note-taking, other methods like graphic organizers, interactive notes, and annotated stickers allowed students to underscore key content graphically during the lesson. Lauren also saved time at the end of class for students to record the “stamp” (the essential conceptual takeaway of the lesson) in their notes.

Lauren’s 11th and 12th graders had had many years of sustained, high-quality note-taking, allowing them to expand their use of their notebooks in new ways. If students got wrong answers on their do-nows or tests, they recorded their mistakes and corrections in the notebook. Her go-to refrain, “Look back at your notebook,” prompted students to see their notebook, not Lauren, as the source for the answer. Her students’ commitment to note-taking has continued past graduation: many of them take their notebooks to college and use them to refresh their conceptual understanding of more advanced coursework.

Build Long-term memory- Use notes for knowledge retrieval.

Build Long-term memory- Use notes for knowledge retrieval.

Brian Smith’s science students are a few years older than Zach’s. They’ve grown used to daily note-taking and many practices, like notebook checks, that keep their note-taking high quality. Brian sees this preparation as a prime opportunity to enhance science content knowledge. One of his strategies is the 30-minute test. “I tell them to take it with just their brain,” Brian says.

Today, there are many excellent examples of this happening within the network. From middle to high school, our science teachers incorporate note-taking into daily instruction, shifting how students internalize information and see themselves as scientists.