Cajsa is a 1st grader at Leadership Prep Bedford Stuyvesant in Brooklyn. In September 2021, after a year and a half of remote learning over Zoom, she started the year as a STEP 1 (Fountas and Pinnell (F&P) Level A), with a reading accuracy of only 83% (90% is a passing score). In just 6 months, she has grown over a grade level in reading, and is now a STEP 6 (F&P Level G).

The key to Cajsa’s meteoric growth? Fluent and automatic word recognition for hundreds of new words. But to teach hundreds of new words in just 24 weeks of schools would have required teaching over a dozen new words every week. With limited time, Cajsa’s teachers needed to accelerate her acquisition of new words – and with a “sounds first” approach, they turbocharged Cajsa’s reading growth.

The challenges that Cajsa faced as a reader during remote learning are the challenges that many students are working to overcome during the 2021-2022 school year. A recent study by McKinsey found that nearly 40% of 3rd graders are 2 or more grade levels behind in reading. Nowhere is this learning loss felt more deeply than for the youngest students, who are just learning to crack the code of phonics for the first time. We’ve seen this firsthand – with 97% of Uncommon kindergarteners below grade level in reading at the end of the 2020-2021 school year, up significantly from 34% at the end of the 2018-2019 school year.

While this data can feel daunting, at Uncommon we believe strongly in the science of reading and take a “sounds first” approach to phonics instruction, where students hear and say the sounds orally before ever seeing a letter or string of letters on a page. This is actually a radical departure from how many of us were taught to read, and is not the norm across early elementary classrooms as evidenced by NYC Schools Chancellor David Banks’ acknowledgement. While Uncommon did not always take a “sounds first” approach, by making the shift fully in 2020-2021, we have seen students at STEPs 3-6 (F&P levels D-G) grow at a rate of 3 or 4 reading levels a year.

What is the Science of Reading?

It’s a pretty catchy buzz phrase in the education world these days, but it really comes down to a basic idea: we should teach students to read based on how our brains learn to read.

Decades ago, two psychologists, Philip Gough and William Tunmer, developed a model of how our human brains learn to read– the simple view of reading. And while we know that reading is anything but simple, it can be boiled down to a basic equation: word recognition, or the ability to turn printed text into speech, multiplied by language comprehension, or the ability to understand spoken language in our everyday or academic conversations. These two factors are the basic ingredients for strong reading comprehension.

“Sounds First”

But we know that these two factors are much more complex than they appear. At Uncommon, we have zeroed in on the first part of the equation, word recognition, which involves the ability to break down sounds, know the spelling-sound correspondences, and recognize words by sight as a key tool for erasing COVID-related learning loss.

There are 26 letters in the English alphabet. But this makes learning to read in English seem deceptively simple. There are actually 44 sounds in the English language that are represented by about 250 combinations of letters. Many of us can probably remember learning that “c” makes a /k/ sound as in “cat”, but not that “c” can help make a /s/ sound in “circle”, a /ch/ sound in “chat”, or a /sh/ sound in “suspicion”.

It’s critical that we focus on sounds first, because letters can actually represent lots of different sounds, especially when we put letters together into combinations. Teaching the sounds first will allow for more flexibility and a wider application of phonics knowledge to nearly all the words our students will encounter in English language texts, including sight words.

Unlocking Sight Words Through Sounds

For decades, teachers have taken flashcards of these high-frequency words like “the,” “and,” and “she,” held them up for students, and made them repeat what they say until memorized. While this teaches most students to recognize those specific words “by sight,” it does not teach any of the sound-spelling correspondences in the word that can give students access to an even larger bank of word knowledge.

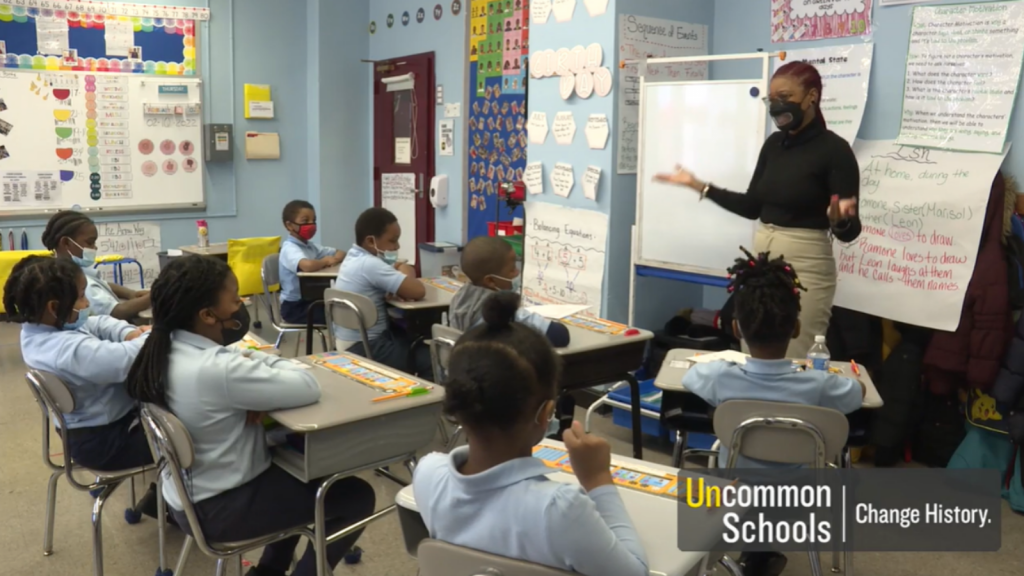

Instead, teachers at Uncommon like Shanika Browne take a “sounds first” approach to sight words that you can see in two clips–one as she teaches the irregular sight word “was” and the other as she teaches the decodable sight word “down.” As you watch Shanika in action, consider:

- What questions does Shanika ask that focus students on the sounds?

- How are the two approaches similar and how are they different?

Shanika does a truly masterful job of asking students to hear the sounds and connect them to a spelling pattern, allowing them to decode that spelling pattern in future words they encounter. For example, by students learning that the /d/, /ow/, and /n/ sounds can be represented by those letters, they can now also access the word “brown,” “now,” and “how” (all on the Dolch list as well) with far more ease. Additionally, while not all sight words follow a clearly decodable pattern as is the case with “was,” teaching words as a combination of sounds represented by letters can accelerate a student to becoming a strong reader. By using this approach, when a student struggles to read a word in a future text, the teacher can now ask, “What sound can [s] make? What sound did it make in [was]?” This “sounds first” approach works as a multiplier effect – giving students the confidence to read dozens of new words without being taught that word explicitly.

Shanika does a truly masterful job of asking students to hear the sounds and connect them to a spelling pattern, allowing them to decode that spelling pattern in future words they encounter. For example, by students learning that the /d/, /ow/, and /n/ sounds can be represented by those letters, they can now also access the word “brown,” “now,” and “how” (all on the Dolch list as well) with far more ease. Additionally, while not all sight words follow a clearly decodable pattern as is the case with “was,” teaching words as a combination of sounds represented by letters can accelerate a student to becoming a strong reader. By using this approach, when a student struggles to read a word in a future text, the teacher can now ask, “What sound can [s] make? What sound did it make in [was]?” This “sounds first” approach works as a multiplier effect – giving students the confidence to read dozens of new words without being taught that word explicitly.

Dean of Curriculum and Instruction Emily Nagel at Leadership Prep Bedford Stuyvesant designed a new approach to sight word instruction based on the “sounds first” approach, in 4 steps:

- Introduce the Word: The teacher says the word orally, has students repeat it, and uses the word in a sentence without evershowing what it looks like on paper.

- Segment the Word: The teacher has students slowly break down the sounds in the word, and count the number of sounds, again without the letters revealed.

- Map the Sounds: The teacher reveals the written word by drawing an empty box with space to represent each sound, and prompts students to say what letters could represent the sound, and then writes the actual letter or letter combination that does represent the sounds.

- Spell It and Write It: The teacher has students say the letter names in order and then write them down.

With limited time and years of growth to make, our youngest students need an approach that multiplies their word recognition exponentially. A “sounds first” approach is exactly what our students need to begin that acceleration as they become lifelong readers.

Click below for PDFs of all the resources referenced above: